At the 2025 Wheat College, Peter “Wheat Pete” Johnson had a wide-ranging discussion with growers that covered growing top wheat by using grower-collected data, factors that impact wheat yields, and how to counter the public perception of agriculture.

Johnson is a former wheat specialist for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs. He is a resident agronomist with realagriculture.com and hosts the weekly podcast, Wheat Pete’s Word.

Before growers got down to business, they enjoyed coffee and doughnuts provided by the Graybeal Group.

Pride in agriculture

Consumers, especially those in urban areas, generally don’t understand what a success story agriculture is. Data collected by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development shows that until about 1960, food production and land use were closely connected — as food production increased, so did the land needed to grow it. But in 1960, food production began to increase much more rapidly than land use. By 2020, growers were producing nearly four times as much food on only about 10% more land, thanks to better genetics, increased use of fertilizer, and weed/pest control.

“Here’s what happens without modern agriculture: population goes up, and food production has to go up or people starve. Those are the only options. Without modern agriculture, the only way that you get that extra food production is by bringing more farmland into production — a lot more land,” Johnson explained.

Unfortunately, there have been some unintended consequences from modern agriculture, especially with nutrient runoff, that need to be recognized, such as algae blooms from phosphorus in the Great Lakes or hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico.

“We have to accept our unintended consequences, and we have to do a better job of explaining the good things that we do,” Johnson added. “If you’re going to have this conversation with a nonfarmer, the first thing you always have to say is, ‘What’s your concern? I understand.’ If you say you’re wrong to the urbanite, they shut down right there. You have to accept that we cause issues, but then, if you can, talk to them about the fact that with modern agriculture, instead of having one person in three in the world food insecure, we now have one person in 10. We’ve had a tremendous positive impact, and I think that we all need to be aware and proud of that impact.”

Factors that impact wheat yields

A study from the National Academy of Sciences has shown that the overall biggest factor in increased wheat yields comes from climate (48%), followed by agronomy (39%), and genetics (13%). Other studies might dispute the genetic versus agronomic advances, but the climate impact is more consistent.

“Sunshine is brighter, and there’s more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Twenty-seven percent of the yield increase you are getting today is because the sunshine has more photosynthetic active radiation in it than it did 30 years ago,” Johnson said. “When it comes to climate, there are three things: it’s sunshine, it’s water, it’s carbon dioxide. But at the end of the day, it’s all about the water.”

According to Johnson, the theoretical maximum number of bushels of wheat per inch of water is 33. Studies have shown that most farmers get an average of seven bushels of wheat per inch of rain. Growers who get better than that tend to be making better use of that water by getting deeper roots and less soil compaction. Organic matter is more important for increasing rooting capability than for its moisture-holding capacity.

“It’s more what (organic matter) does for that plant to have better rooting and better water migration to the plant,” he said. “If you’re in a heavy clay soil, water doesn’t move to the plant very fast, and sometimes, you can have great moisture in deep profiles and the roots will never get to it. If you can increase your organic matter, you get better rooting depth.”

The highest wheat yields in the world tend to come from two locations — the United Kingdom and New Zealand — because their temperatures are cooler overall thanks to the moderating effects of being surrounded by water. Heat is the number one enemy of high wheat yields; the longer the grain fill period and the longer the plant stays green through grain fill, the better the yield potential. On average, growers lose one bushel of wheat per acre per day for every day that the temperature goes over 77 degrees F during grain fill.

“Wheat is a cool season crop. The perfect day of the wheat crop’s life is a 65 degree day and 50 or less at night (but above 32 F). That’s when you’re going to get maximum production,” Johnson explained. “If you could get your wheat into that critical period with those temperatures, you are going to blow the doors off from a yield perspective. If you can get your crop to head out earlier, you’re going to get more of that grain fill period in those ideal temperatures, and you’re going to get higher yields.”

YEN-ing

Johnson closed out his presentation by talking about the Great Lakes Yield Enhancement Network (YEN). The YEN takes yield data from farmers’ crops and tries to figure out what a high-yield grower is doing differently than a lower-yielding grower. What makes the YEN different from a simple yield contest, however, is the calculation of a grower’s yield potential. The Great Lakes YEN includes farmers not only from the Great Lake states and Ontario, Canada, but states like Missouri, Kentucky, New York, and, for the first time, a farmer from Eastern Washington, Jesse Brunner.

“The percent of potential lets you, as a grower, assess yourself against your potential as opposed to the guy with the better farm,” Johnson said. “And that is really, really cool. We also collect a lot of data and do a lot of networking. Farmers talk to each other, and we are talking to each other across huge geographies.”

Yield potential is calculated by taking into consideration rainfall, soil-available water, and solar radiation, among other factors. At the end of the growing season, YEN growers get reports that compare their yield and input data against other members. Using Brunner’s report as an example, Johnson quickly pointed out some of the differences between the Eastern Washington grower’s methods and the other growers in the YEN before leaving to catch his flight back to Canada. Before he left, though, he put in a plug for growers to start their own YEN.

“I hope you will consider joining the YEN because we’d love to have more Washington state growers, but I also hope you will consider doing your own YEN, because there’s so much variability in Washington state that I really think you can move the bar forward if you do that,” he concluded.

Johnson’s podcast is available at realagriculture.com/wheat-petes-word/. He also appears on a video series, Wheat School, which tackles every facet of the wheat growing season. Those videos can be found at realagriculture.com/wheat-school/.

Updates and rotational topics

Following Johnson’s presentation, growers heard industry updates from Derek Sandison, director of the Washington State Department of Agriculture; Wendy Powers, current dean of Washington State University’s (WSU) College of Agricultural, Human, and Natural Resource Sciences; Kevin Klein, chairman of the Washington Grain Commission; and Jeff Malone, president of the Washington Association of Wheat Growers.

After lunch, Aaron Esser, WSU Extension agent and the Adams County Extension director, talked about nutrient management as a critical component to high yielding wheat. One of his main points to growers was if they don’t measure something, they can’t manage it. Some nutrients, like nitrogen (NO3), sulfur, boron, manganese, and chloride are mobile in the soil. Potassium, calcium, molybdenum, and cobalt are somewhat mobile in the soil, while phosphorus, magnesium, and iron are not mobile. In the plant, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, and chloride are mobile, but sulfur, calcium, boron, copper, manganese, zinc, and iron are not.

“So, if you’re looking at when plants need these nutrients, if these aren’t moving in the plant, if it takes it up the wrong time, then it’s not very useful to the plant. And when you’re starting to go out and look at the deficiencies and symptoms to try to diagnose what’s going on, understanding if it’s mobile or immobile in the plant and where you’re seeing the deficiencies can be pretty important,” he said.

Esser talked about soil pH, and how closely it’s linked with nutrient management. He also touched on the potential impacts of residue removal.

“When you start taking the residue off, you also should be applying lime onto your fields. Just for a general rule of thumb, for every pound of nitrogen you put on your soil, you need about two pounds of calcium carbonate to neutralize it. You remove the residue, and that two pounds becomes four pounds of calcium carbonate you need,” he explained. “If you’re getting payments for your straw, make sure it’s going to be adequate enough to take care of all those hidden expenses with removing it.”

Growers have access to multiple tools and calculators on smallgrains.wsu.edu to help them figure out how to manage nutrient applications. Esser encouraged growers to do both soil and tissue samples regularly to build up a picture of what’s happening in the field. Growers should consider variable rate applications based on multiple years of data. Esser’s approach is to manage the top yielding 22% and the bottom yielding 22% of his fields differently.

“Set up realistic yield goals based on moisture and historical yields,” he said. “We all like to be the highest yield around, but make sure you still can remain realistic, don’t be afraid to push, but you have to do it with a sense of a framework. Soil sampling, crop nutrient removal, and nitrogen uptake efficiency can be valuable to monitor and make improvements moving forward.”

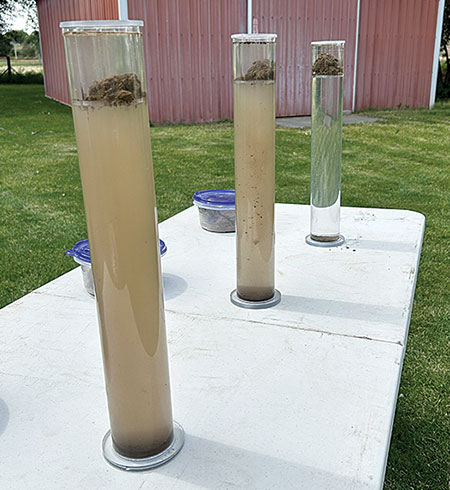

Following Esser’s presentation, growers split into groups for the rotational topics, which included seed treatments by Ric Wesselman from Syngenta; a drone demonstration by Terraplex Pacific Northwest Drones; and a soil moisture retention demonstration from the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

AMMO sponsors

Thank you to these industry stakeholders who help make the Agricultural Marketing and Management seminars possible:

AgWest Farm Credit

Almota Grain

Farmland Company

HighLine Grain Growers

JW & Associates, PLLC

Northwest Grain Growers

Patton & Associates LLC

PNW Farmers Cooperative

Syngenta

The McGregor Company

Washington Grain Commission