Cover crop conundrum Wheat industry would like to see definition of cover crops expanded to include winter wheat

2025March 2025

By Trista Crossley

Editor

With the last administration’s push on climate-smart practices, a lot of attention has been focused on cover crops. But how do you implement a cover crop if your cash crop is winter wheat, and you don’t have many other rotation options?

The answer, according to Jake Westlin, vice president of policy and communications for the National Association of Wheat Growers (NAWG), is to get the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to issue a technical note that the environment benefits of winter wheat are similar to a cover crop, but doesn’t require termination before harvest, a key requirement of cover cropping.

“That would provide a solution that growers could have a cover crop, but they could also do winter wheat, which has similar environmental benefits to a cover crop, and they could bring it to harvest,” Westlin said.

According to NAWG’s policy guidelines, winter wheat, planted in the fall and harvested the following summer, provides a living cover and root system over winter, similar to a cover crop. In fact, winter wheat is a cover crop under NRCS conservation practice standard 340 for cover crops, but it cannot be harvested. A harvested winter wheat crop provides the same or more carbon sequestration because the wheat taken to grain harvest is in the ground longer than a terminated cover crop. Winter wheat, whether part of a rotation for harvest or terminated as a cover crop, provides environmental benefits including reducing nitrogen losses, interrupting pest cycles, sequestering carbon and improving soil health. Reduced tillage systems that leave standing wheat residue result in increased water infiltration due to the durable crop residue left in the field. The benefits provided as a crop for harvest are the same — if not better — than those of a traditional terminated cover crop. These benefits should be more broadly recognized by climate smart programs and government policy.

The wheat industry is concerned that tax credits, such as the Clean Fuels Production (45Z) tax credit, or some NRCS programs that require a cover crop may disincentivize wheat production, leading to a loss of wheat acres in the U.S.

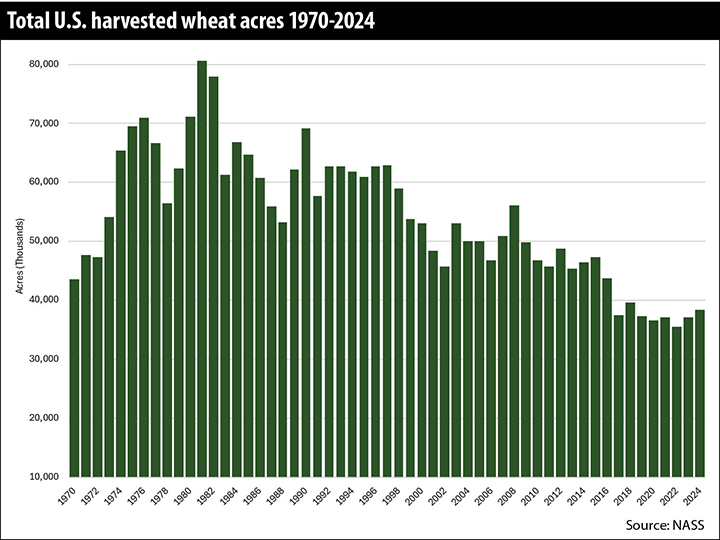

“If growers move away from wheat production, what is the long-term viability of wheat in the U.S.? Are we going be a major exporter? Are we going to continue to see a decline in (wheat) acres and see winter wheat acres shift to something else?” Westlin asked.

According to the National Agricultural Statistics Service, more than 82.8 million acres of corn, 86 million acres of soybeans, and 38.4 million acres of wheat were harvested in the U.S. in 2024. For wheat, that’s more than a 50% decrease from its high of 80.6 million acres in 1981.

The change could also be relevant to growers because of carbon initiatives being pushed by some states, such as Washington and California.

“At the state level, there’s a lot of low carbon fuel standards they’re looking to put forward. So that could be a factor,” Westlin added.

In the drier rainfall regions of Eastern Washington, the worry isn’t so much that winter wheat acres will shift to another crop, but that there’s some evidence that cover crops grown during a fallow year take moisture away from the following winter wheat crop. And if growers can’t grow a cover crop, they may be ineligible for some benefits, such as lower crop insurance subsidies, premium relief on crop insurance, or the ability to participate in sustainably grown marketing opportunities.

In September 2024, armed with research from Kansas State University that supported winter wheat as a cover crop, Andy Juris, a wheat grower from Bickleton, Wash., and past president of the Washington Association of Wheat Growers; NAWG President Keeff Felty; and Kansas wheat grower Chris Tanner met with Ag Secretary Tom Vilsack to discuss the issue. Their message was that growers in drier regions didn’t necessarily need the incentive payments for cover crops, just the ability to grow a crop that is classified by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as a cover crop.

“We emphasized that if you look at what the USDA classifies as a cover crop, winter wheat checks every single box,” Juris said. “Some of these other cover crops aren’t food crops. They are just something designed to hold the soil down or to add organic matter or whatever. Here’s a crop that accomplishes all of that in addition to being a food crop.”

Juris said that USDA’s main concern seemed to be that producers who receive incentive payments for planting a cover crop that is then harvested as a food crop are “double dipping.” Vilsack and the USDA agency representatives that the group met with were receptive to growers’ message about changing the definition of cover crops to include winter wheat.

“When we look at it from Washington’s perspective, the viability of just wheat in general as a crop, a lot of us are limited in what we can grow. If we are going to see incentives for cover crops come out that do not allow us to participate, that is disappointing,” Juris said.

Both Juris and Westlin said that even if the new administration doesn’t have the same focus on climate and climate-smart practices, they would still like to see the issue resolved for the future. Although that solution could be done through the farm bill, NAWG would rather see it come via an NRCS technical note.

“We don’t want to overprescribe or put unnecessary guardrails around that situation if we’re legislating it,” Westlin said. “We’re confident that we can fix this administratively, since it that’s kind of where this originated.”