Pesticide Perspectives Are pesticides good or bad for consumers, and what goes into pesticide safety?

Further Reading2024

By Jennifer Ferrero

Special to Wheat Life

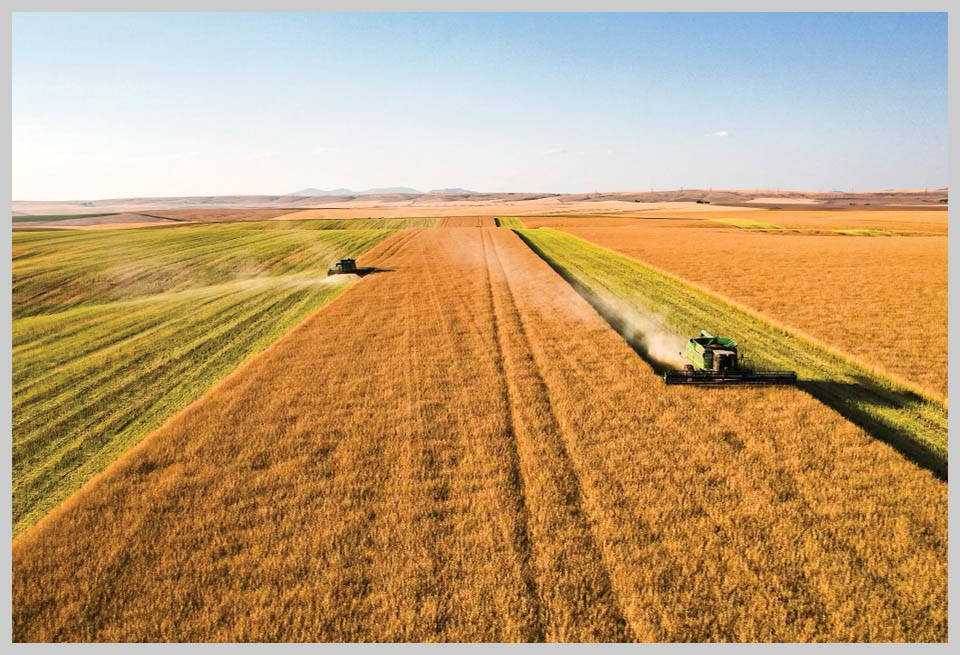

Wheat fields in Washington can be home to many insects, weeds, and diseases. Producing quality food crops requires intervention. Many factors are at play in the realm of safety for humans and the environment, including using insecticides, herbicides, or fungicides. In this article, we refer to all these types of products generally as “pesticides.” It’s a complex picture that affects global crop output from the state and our long-term environment and economy. The big questions for consumers are whether pesticides are bad, whether they are necessary, and how pesticide use, or nonuse, impacts our economy.

In Washington, the use and application of pesticides are well-researched, supported, and regulated. Ensuring safety for humans, the environment, and long-term crop sustainability is a function of government, the farming community, university researchers, and third-party players like the Washington Grain Commission (WGC).

As food-buying consumers, we ingest published information from the ever-expanding media regarding pesticides like Roundup and other chemical interventions and wonder if they are bad for us.

Washington State University (WSU) has a deep infrastructure in researching what’s bugging our crops. The WSU Extension Dryland Cropping Systems Team offers disease, soil and water, insect, and weed resources for wheat farmers and the collective industry. They deal in wheat and small grains and collaborate with educators and faculty. According to smallgrains.wsu.edu, “Together, they work to efficiently coordinate and deliver educational information and resources to dryland crop producers. The team includes specialists in plant pathology, entomology, weed science, soil fertility, economics, agronomy, variety selection, and communications.” In other words, they take a science-based approach to understanding and supporting crop producers.

Ben Barstow, a 30-year grower, commissioner, and chairman of the WGC, also takes a scientific approach to farming. Barstow has a bachelor’s degree in plant protection from the University of Idaho, a master’s degree in entomology, and is interested in the chemistry of soil and plants. He also maintains a private pesticide applicator’s license for Washington.

Barstow said crops, weeds, insects, and diseases change or evolve from season to season, as does their susceptibility to pesticides. “These all are living organisms that continue to evolve and change,” he said. When Barstow started farming, “There was a steady flow of new chemistry that we could count on to solve pest problems,” referring to the new pesticides discovered and commercialized between the end of WWII and the 1980s. He said only one new product has been released since then, and “what worked five years ago is probably not going to work five years down the road” due to ongoing evolution. He said that pest control products have been vilified, and none of the growers he knows like to use them, but everyone wants to produce safe, clean, high-quality food.

“And we need pest control products to do that. Everyone is looking at alternatives besides chemistry to control these things. I’d rather use a disease-resistant wheat variety and not use a fungicide; that’s an extra cost,” he explained. Barstow has leaned on using new wheat varieties bred for disease and pest resistance but said it is not a replacement for using pesticides. But he also uses these products safely as directed by the pesticide label.

The Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA) manages the safe use of pesticides in Washington. They offer the required licensing and recertification for growers along with pesticide compliance programs. There are four key program managers for pesticides in the WSDA; we spoke to two of them: Christina Zimmerman and Scott Nielsen. They help educate, license, and regulate state pesticide use. Zimmerman’s role includes initial licensure and continuing recertification of pesticide applicators, distributors, consultants, and structural pest inspectors. Her program administers pesticide licensing exams, maintains exams, and accredits courses for continuing education credits.

There are 33 exams in the state, with six available in Spanish. Zimmerman said her program has 10 staff members and oversees 24,000 active licensees in Washington. Nielsen’s group has about 20 staff members, including field investigators, quality assurance, administration, and others. Nielsen’s compliance staff conducts inspections and complaint investigations of pesticide storage, distribution, and applications across the state and enforces state and federal regulations.

Becoming licensed and maintaining a license for the safe use of pesticides comes with coursework, continuing education credits, and testing. Also, those licensed may be subjected to an audit of their practices by WSDA.

Both Zimmerman and Nielsen said the management and regulations are for human health and environmental protection. They said that if not used safely, per the label, and with personal protective equipment, pesticides can impact health and the health of others, including the agricultural community and others in the supply chain. Because they regulate pesticide use, it helps water and soil stay safe and contributes to the safety of the applicators, laborers, and their families.

“The greatest risk is to the person mixing and loading the sprayer because they are handling the concentrate,” Barstow echoed. “But the toxicity of the concentrate on some of these products is similar to table salt. Everything else is exposed to the diluted volume.”

He shared that GPS guidance greatly reduces pesticide overapplication when farmers spray a field. “It’s a huge improvement. With GPS-guided and controlled sprayers, if the boom overlaps where you have already been, it stops spraying — it saves 5-7% of a pesticide product. Cost-wise, buying the GPS equipment only takes two to three years to pay off.” Barstow loves having the GPS guidance because it eliminates guessing and overapplication. He tells his grandkids, “It’s like driving Mario Cart all day long … except there are no explosions.” New tractors and combines are self-driving using satellites, complex computer systems, and the Internet.

“We use herbicides designed to kill plant cells,” Barstow said. Being able to disrupt the chemistries of certain cells but not others is the science of pesticides, herbicides, and insecticides. The chemical pathway targets of herbicides are often not the same chemical pathways found in human or animal physiology. “Animals won’t be harmed by many of the herbicides being used. Animals like mice, birds, dogs, and cats don’t care.”

Barstow uses modern wheat varieties. He also uses certified seed. He said herbicides are still used, but he uses them safely and per his licensure with the state. He said that Roundup is only active when sprayed on plants; it becomes inert once it contacts the soil. Also, each year, he assesses the chemistry of his soil to determine which inputs and exactly how much of each to apply. Getting the input variables right is part of the formula that maximizes our yield and economic potential, allowing the U.S. to be a top contributor to dinner tables around the globe.

Barstow said bakers and wheat flour millers need high-quality wheat with consistent performance to produce consistent food products. He is proud to grow safe, dependable, and reliable high-quality wheat that helps feed the world.