A Whitman County stream, parts of which run dry in the summer, is causing tensions between landowners and the Washington State Department of Ecology (Ecology).

Whitman County landowners who own land along Spring Flat Creek are being told by Ecology that they are polluting the waterway and will have to take steps to remedy that — mainly by putting in riparian buffers — or face hefty fines. Landowners want to see the water quality data Ecology has gathered that proves the agency’s case.

Background

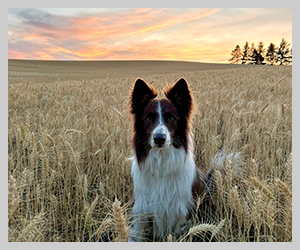

Spring Flat Creek runs between Pullman and Colfax, Wash., and drains approximately 13,200 acres of primarily dryland agriculture and rangeland. Much of the creek runs parallel to Highway 195 and doubles as a roadside ditch in some places. The creek meets up with the South Fork Palouse River just outside of Colfax, where the concrete flood control channel begins. Much of the upper portion of the waterway is considered an intermittent creek, with the majority of water that moves down it coming from snowmelt or heavy rainstorms. During summer, the water in the creek tends to be stagnant with little flow, while in the upper reaches of the watershed, the creek is completely dry.

In August of 2024, Ecology published a straight to implementation strategy internal work plan for Spring Flat Creek to address three things that Ecology says don’t meet the state’s water quality standards (especially for aquatic life): temperature, low dissolved oxygen, and high pH.

The most well-known option for a water cleanup plan is a total maximum daily load (TMDL) calculation, but there are a few other options that are less time consuming and expensive, such as the straight-to-implementation (STI) effort, that can get to cleaner water faster.

“Straight to implementation is a strategy that we use in particularly small watersheds where the sources of pollution are nonpoint, and the fixes are readily identifiable,” said Chad Atkins, watershed unit supervisor for Ecology’s Eastern Region Office. “The problems and the fixes are well known, and we feel like we can get to clean water without having to do a really significant investment in a TMDL.”

In Spring Flat Creek’s case, Ecology has determined that “all violations of water quality standards are the result of land uses that cause nonpoint pollution,” such as agriculture and stream channelization. There are no point source dischargers on Spring Flat Creek. Ecology concluded that the water quality failures are primarily due to:

- The lack of low soil disturbance tillage practices (direct seed and no-till) in upland crop production areas.

- The lack of appropriate setbacks/buffers from adjacent land uses on watershed streams.

- The lack of appropriate setbacks/buffers from adjacent land uses along stormwater conveyance features.

- Inadequate/poor riparian condition and structure throughout the watershed.

Ecology identified approximately 345 riparian acres of Spring Flat Creek as being used for dryland crop production; 88 riparian acres being impacted by livestock; 47 riparian acres are in perennial grasses; and 34 riparian acres are roadways or impervious surfaces. In all cases, Ecology’s best management practices point to woody buffers as the best solution, followed by conservation tillage and residue management in the case of dryland crop acres. While buffer widths may vary depending on the channel width, growers are likely looking at a minimum of 60 feet on each side of the creek beginning from the ordinary high water mark.

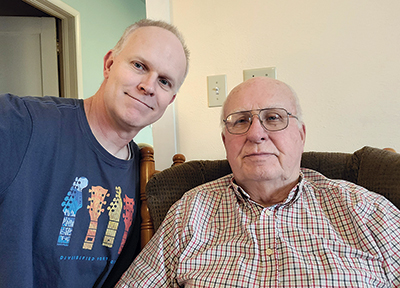

What the growers say: Steve Germain

In mid-2023, Germain received a call from Ecology with some disturbing news. Germain, whose father owns just over 100 acres near the headwaters of Spring Flat Creek, was told his father would have to put in 100-foot buffers immediately and be solely responsible for the cost of building and maintaining them. The family rents out their ground to a local farmer who grows wheat, garbs, and peas. The farmer direct seeds with one tillage pass every three years. Due to his father’s health issues, Germain has been communicating with Ecology on this issue.

When Germain pressed for more information, he was directed to the Revised Code of Washington that simply states one is not allowed to pollute any waterway in the state of Washington. The Ecology employee told Germain that a field condition evaluation had been done, and Germain filed a public records request to find out exactly what information had been collected. He said it consisted of six pictures taken from the road right after spring runoff and a spreadsheet with values in it, but no real information. Through emails, Germain kept pressing for more information.

“He (the Ecology employee) continued to point back to the RCW, point back to the ‘your dad has to do this right now, or there’s going be fines against your dad from the Department of Ecology,’ and I just kept saying that I needed more information,” Germain said. “You need to tell me what the criteria is. Where are your water tests that show what’s going on in Spring Flat Creek? Because I knew and all the farmers will tell you, that Spring Flat Creek, especially at the headwaters where my dad’s farm is, is dry nine months out of the year. They had taken their field evaluation at the right time in March, right in the middle of spring runoff so they could get these pictures that show water running through drill tracks. It was very frustrating because it really felt like they were gathering information and making decisions based on very broad strokes.”

Another thing that troubled Germain was he was being told that riparian zones would have to be established up in the draws away from the creek. Two years later, he said he still hasn’t seen any reports that clearly spell out what is happening in the watershed with data to back it up.

In October 2024, Germain received a warning letter from Ecology. The letter told him to contact the department to discuss his options for resolving the issue or face fines. At this point, Hallie Ladd had taken over as Ecology’s Palouse Water Implementation lead. Germain said he exchanged emails with Ladd, once again requesting information, but received no solid answers.

In December 2024, Ecology held a meeting for Spring Flat Creek landowners. Germain said growers were told, again, that they needed to work with Ecology and the local conservation districts to come up with a plan to install riparian buffers. Ecology also disclosed that there was some funding available to help install the buffers, as well as funding to compensate growers for the land that would be taken out of production. However, the amount of funding and how long it will last was unclear.

For Germain, who had read Ecology’s STI internal work plan, one thing stood out. According to the plan, the STI strategy does not include an initial water quality study to establish baseline conditions and to model the load reductions needed.

“So, the one question I had at the meeting was, if you have no baseline to establish what the pollutant is, much less what was going on before the pollutants started, how are you going to base the results of your implementation plan on that?” he said.

Another concern raised at the meeting came from a Farm Service Agency employee who pointed out that if riparian zones are installed, that acreage could be permanently lost from a farmer’s baseline acres.

“In effect, they are saying that once you take that land out of production, you can never get it back,” Germain said. “That’s plain dirty there, especially knowing that Spring Flat Creek is empty nine months out of the year. I understand that you’re going to get runoff in the wet parts of the year; that’s why we have storm drains.”

At the meeting, Ladd told landowners where on Ecology’s website they could find data from water sampling sites along Spring Flat Creek. Germain found a site just downstream from his family’s property, but it showed that no information had been gathered for that site. Germain confirmed that fact with Ladd in January 2025. That was Germain’s last contact with Ecology. He is concerned that once the buffers are installed, there’s no guarantee that Ecology won’t come back and ask for more.

“There’s no facts that any of what they’re asking the farmers to do is really going to make an impact,” he said. “The pros of it are that they’re trying to protect water, and I agree with that. I think we do need to do our part. The cons of it are they’re not giving any data to say that what they want the farmers to do will really impact the water. This is them really using any means they feel necessary to move their agenda forward at the cost and impact to the farmers.”

What the growers say: Craig Kincaid

The Kincaids grow wheat, canola, and some chickpeas using a mix of conventional tillage and direct seeding. One of their fields borders Highway 195 and has about a half mile of Spring Flat Creek running through it. Kincaid got his initial letter from Ecology in July 2023.

“The letter kind of came out of the blue,” he said. “Obviously, it’s a visible stream, and I think it’s probably why it was targeted. I don’t know that it would have any higher priority than any other watershed. It’s not unique in my opinion. I think its proximity to the highway makes it an easy target.”

Like Germain, Kincaid said the creek tends to have minimal water in it in summer and fall, and he’s never seen any fish in there. He acknowledges that the creek could benefit from some riparian zone work, but doesn’t think that the buffers Ecology wants are the only answer. In fact, he believes that if his family were to install Ecology’s buffers, they would cause more problems.

“What Ecology wants is 60-foot buffers on both sides of the stream, and they want them covered in bush and trees. That’s really where, at least for us, the problem lies,” Kincaid said. “The trees will make doing ditch maintenance pretty much impossible. We will end up with a giant flood plain. And not only that, but we have bridges that cross the creek. We have lots of access points. All these things that’s going to cause a ton of trouble when we can’t keep that ditch clean. We know we will have to do something, maybe, but does it need to be their way? What if a 15-foot grass buffer strip would accomplish what they wanted?”

Kincaid anticipates that if the creek starts spreading out and flooding, the fields surrounding the area won’t be able to drain as well and will become less viable for farming. He was also at the December meeting in Colfax, where he said Ecology didn’t provide any additional answers.

“They say there’s a problem, but I haven’t seen any information, any actual testing information. They tell you they have it, but they haven’t produced it, to my knowledge,” he said.

Ecology’s response

According to Atkins, before Ecology performs a watershed evaluation, data has been collected that confirms that the watershed is polluted. In the case of Spring Flat Creek, that data dates back to 2006 when the department began establishing TMDLs for the South Fork Palouse River Watershed. In 2023, Ecology prioritized the Spring Flat Creek watershed and performed a watershed evaluation, where department employees visually inspected the waterway from public roads and documented conditions that the department says are known to cause nonpoint source pollution, such as gully formation; signs of sheet and rill erosion; and destabilized banks from tillage practices.

“We use specific criteria that the science tells us is associated with pollution, and then we go out in the watershed, and we prioritize parcels where pollution is occurring,” Atkins said. “We’ve done an exhaustive review of the science at our agency on things like riparian health and tillage practices. That science has identified those criteria that we use in the field. It’s a combination of past experience as well as a really thorough review of the existing literature.”

Watershed evaluations were also done in 2024 and 2025. Ladd said the evaluations generally happen in the spring.

“We’re looking at the runoff that is typical of the pollution that we’re looking at for nonpoint sources, and it helps us document and tell our story and also explain to the landowners or the producers what we’re seeing that is contributing to pollution of the water body,” Ladd said.

Ten landowners in the Spring Flat Creek Watershed have been notified by Ecology since 2023 regarding nonpoint source pollution.

Ecology has a database that shows water quality monitoring, current and historic, and includes data on Spring Flat Creek. The data includes Ecology’s own data and data submitted to them. The department has five data point collections on Spring Flat Creek: a groundwater monitoring well near Landfill Road and Highway 195 and four on the south end of Colfax, where the creek enters the flood control channel. The mapping system the agency uses also shows a monitoring point near where Carothers Road joins Highway 195, but as Germain pointed out, it has no data associated with it; Ecology confirmed that it is not one of their sites.

Atkins and Ladd pushed back on landowners’ claims that Ecology has not produced data that proves farmers are causing problems in the watershed and therefore can’t establish a baseline to track improvements.

“I think there’s a misperception that if we grab a sample, that tells us where the pollution is coming from,” Atkins said. “That’s not the tool that the science tells us is most useful to identify pollution sources; that is our watershed evaluation work. We go out and identify pollution sources using that tool. Our straight to implementation plan has a monitoring strategy built into it. We will be doing monitoring work as we implement improvements in the watershed to see where we stand.”

According to Ladd, Ecology is finalizing a grant with the Palouse Conservation District to collect data at monitoring stations along the creek. That data collection will include stage height, water temperature, and dissolved oxygen and is designed to monitor the watershed as a whole, not individual parcels or properties. However, Atkins cautioned that Ecology doesn’t expect the best management practices that farmers implement to affect water quality data immediately.

“Nonpoint pollution is episodic. It’s dynamic. It’s accumulative. It takes time for the benefits of those efforts to be realized in the data,” he explained.

Ecology is standing firm on what they want done along the creek. Atkins said buffers less than the minimum width — 60 feet on each side — or grassy strips will not meet Ecology’s best management practice requirements. In cases where the buffers make it hard to farm an area, such as between the buffer and a road, the department will work with the landowner to come up with a strategy.

Despite the intermittent nature of Spring Flat Creek, it still falls under Washington’s definition of “waters of the state.” So do the creek’s ephemeral draws. Ladd said the department isn’t ruling out requiring riparian buffers in the draws, but those would be site specific.

“Right now, for Spring Flat Creek, we are focusing on the main stem. However, if there’s other practices, like converting to no till that could help with the erosion of those draws, or if I’m on-site with a landowner and we could see that the draw is heavily eroded and is contributing significant sediment to the main stem of Spring Flat Creek, we’d want to work with them to also protect that area to help reduce pollution,” she said.

There is funding for landowners to install and maintain the riparian buffers. There’s also a buffer incentive plan that pays up to $350 per acre per year for land in the buffer; however, that’s only available if the full riparian management zone is buffered. Producers who install just the minimum 60-foot buffer will get paid up to $300 per acre. Contracts will last for 15 years. Although the work is funded by Ecology, landowners will work with the local conservation districts.

Ladd said she will continue to follow up with Spring Flat Creek landowners through phone calls and emails. She anticipates sending out more letters after analyzing the results of the 2025 watershed evaluation. Regarding the warning letters some producers have already received, enforcement action isn’t necessarily the next step.

“We haven’t made any decisions in that regard, and we want to absolutely continue to work with people and are committed to getting out there, doing site visits and working with them to protect water quality,” she said. “I just want to make it clear that we will continue to work with them. I know there’s a lot of questions out there, and (producers) can contact me at any time. I’m happy to talk with them on the phone, email, do a site visit, if welcomed.”

“We recognize that agriculture is an important industry in the state, and we believe strongly that we don’t have to choose between clean water and a healthy agricultural industry,” Atkins added. “That’s in our minds as we go about doing our nonpoint work. Those two things do not need to be mutually exclusive, and we have lots of examples, statewide, where water quality is being protected, and we have productive farms and ranches.”

To see data collection points on Spring Flat Creek, not all of which are Ecology’s, go to apps.ecology.wa.gov/waterqualityatlas/wqa/map. Click on “Add/Remove Map Data” on the left. In the Map Layers box, select “EIM Locations” and click on the go button. Zoom into the area you are interested in. The data point collections are represented by little squares; click on one to see information associated with it.