With wheat prices hovering north of $10 per bushel, wheat growers may look like they are doing pretty well, but appearances can be deceiving as rising production costs keep eating away at producers’ profits.

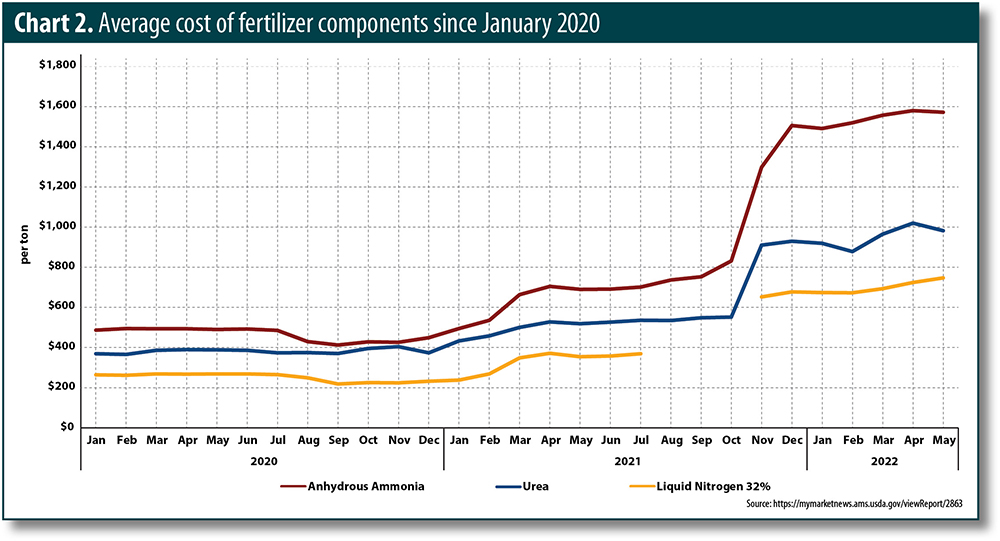

According to U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates, total U.S. production expenses increased 5.5 percent from 2021 to 2022, on top of an 11.5 percent increase from 2020 to 2021. Fertilizer saw an especially big jump. From 2020 to 2021, fertilizer prices rose 16.5 percent; from 2021 to 2022, they jumped 12 percent.

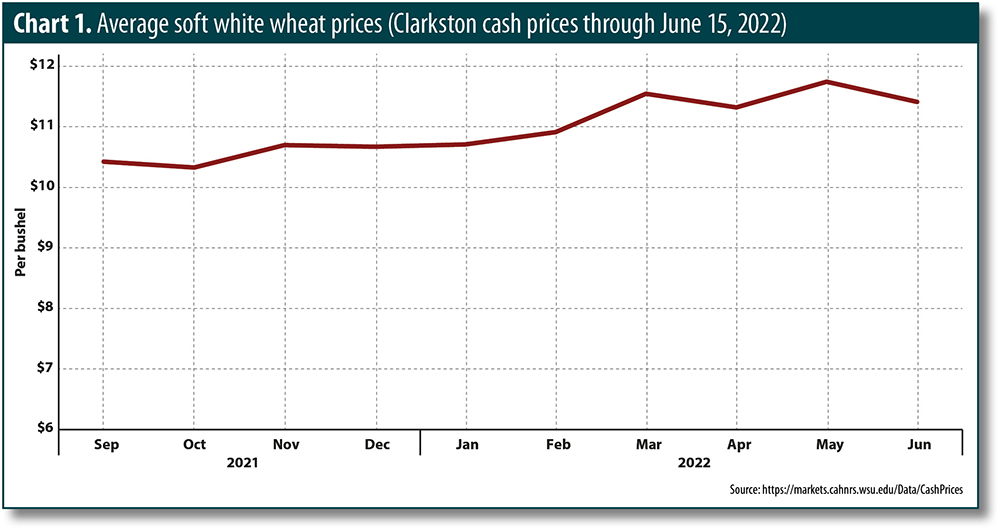

Many of the same issues that are pushing wheat prices higher (limited global supplies, the war in Ukraine, weather and production issues) are also pushing input costs higher. Randy Fortenbery, holder of the Thomas B. Mick Endowed Chair in Grain Economics at Washington State University, pointed out that white wheat prices haven’t changed much since November of 2021 compared to the changes in the cost of inputs (see Chart 1).

“White wheat prices were already pretty good last fall, so prices have not gone up as fertilizer prices have gone up for white wheat producers in the Pacific Northwest,” he explained. “White wheat prices really have only been in a 50-75 cent range for eight months, and fertilizer prices have gone up a lot over that period of time. Prices look high, but input costs are even higher.”

“White wheat prices were already pretty good last fall, so prices have not gone up as fertilizer prices have gone up for white wheat producers in the Pacific Northwest,” he explained. “White wheat prices really have only been in a 50-75 cent range for eight months, and fertilizer prices have gone up a lot over that period of time. Prices look high, but input costs are even higher.”

Producers vary in the fertilizers that they apply to their fields, but three common ingredients are anhydrous ammonia, urea and liquid nitrogen, and all three have seen prices rise. Based on Iowa data from USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (USDA often uses Iowa prices as representative for the U.S.), anhydrous ammonia was $1,571.80 in May of 2022, up from $689.25 in May of 2021. A ton of urea cost $981.54 in May of 2022, up from $518.23 in May 2021. Nitrogen was $746.61 in May of 2022, up from $354.40 in May 2021 (see Chart 2).

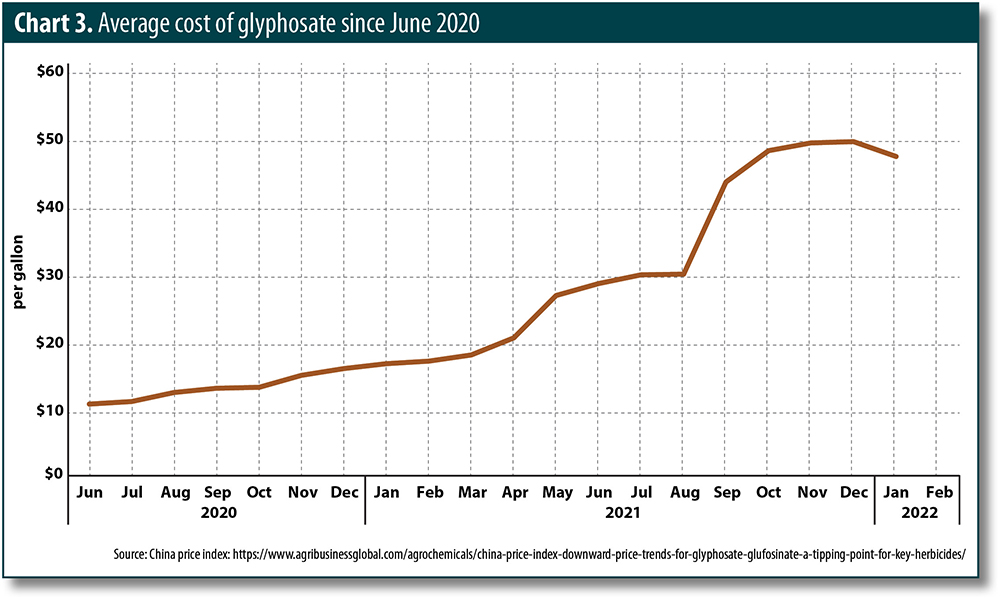

Glyphosate is a critical tool that producers use to control weeds, especially in no-till cropping systems, and China is the world’s largest producer of glyphosate. According to the China Price Index, found at agribusinessglobal.com, the wholesale price for glyphosate in June 2020 was $11.20 per gallon. In February 2022, the price had quadrupled to $44.87 per gallon (see Chart 3).

Glyphosate is a critical tool that producers use to control weeds, especially in no-till cropping systems, and China is the world’s largest producer of glyphosate. According to the China Price Index, found at agribusinessglobal.com, the wholesale price for glyphosate in June 2020 was $11.20 per gallon. In February 2022, the price had quadrupled to $44.87 per gallon (see Chart 3).

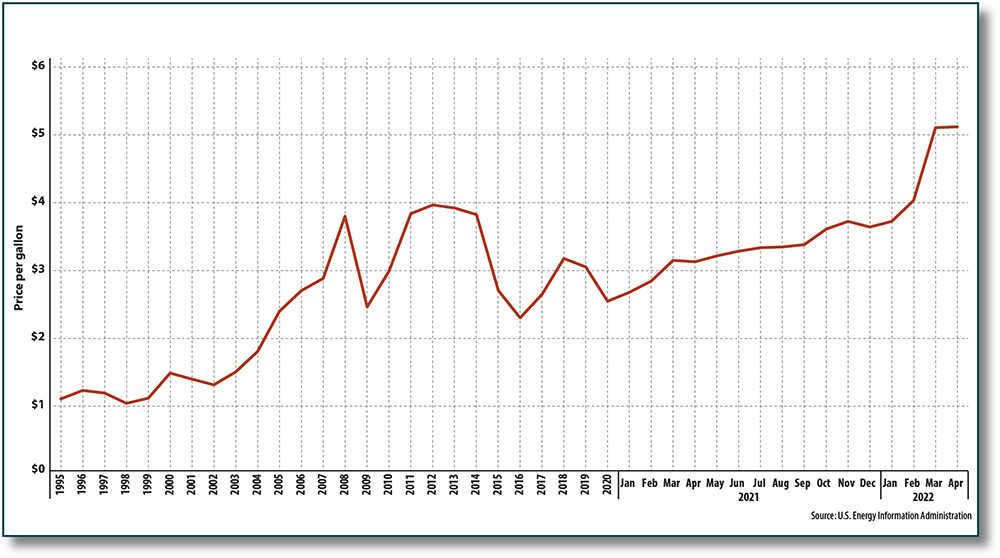

Fuel, particularly diesel, is another major expense for wheat farmers. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the average U.S. price for a gallon of No. 2 diesel in 2020 was $2.55. In April of 2022, it was $5.12 per gallon (see Chart 4).

Fuel, particularly diesel, is another major expense for wheat farmers. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the average U.S. price for a gallon of No. 2 diesel in 2020 was $2.55. In April of 2022, it was $5.12 per gallon (see Chart 4).

Fuel, fertilizer and chemicals aren’t the only inputs that are hurting producers’ bottom line. Other costs have gone up as well, such as seed and interest rates on production loans. It’s difficult to calculate just how much profit producers are actually making, because there are so many variables that have to be taken into account, and every producer’s situation is different. But on the whole, industry stakeholders agree that the current high wheat prices aren’t translating into fat bank accounts for producers.

Fuel, fertilizer and chemicals aren’t the only inputs that are hurting producers’ bottom line. Other costs have gone up as well, such as seed and interest rates on production loans. It’s difficult to calculate just how much profit producers are actually making, because there are so many variables that have to be taken into account, and every producer’s situation is different. But on the whole, industry stakeholders agree that the current high wheat prices aren’t translating into fat bank accounts for producers.

The Agricultural and Food Policy Center (AFPC) at Texas A&M University published a report in May 2022 analyzing the economic impacts of higher crop and major input prices based on 64 representative farms, including 11 wheat farms, three of which are in Eastern Washington (afpc.tamu.edu/research/publications/files/716/BP-22-06.pdf). The report found that wheat farms are facing an average reduction in net cash farm income of $399,000 from 2021 to 2022. That’s an average decline of $83 per acre. The authors also noted that:

• A major point of reference for the report — net cash farm income in 2021 — included a significant amount of ad hoc assistance. Absent another infusion of assistance in 2022, they estimate that significant increases in input prices will result in a huge decline in net cash farm income in 2022 (compared to 2021).

• Despite the significant reduction from 2021, high commodity prices will likely still result in positive net cash farm income for most of AFPC’s representative farms.

• Much of their analysis hinged on producers being able to lock in high commodity prices at average yields. With drought ravaging half of the country (and many other areas facing excess moisture), this assumption may be overly optimistic.

The full impact of rising input costs may still be coming, as Fortenbery pointed out.

“One of the challenges right now is the winter wheat was all planted last fall. Fertilizer prices have been going up dramatically for quite a while, but they weren’t as high last September as they are now,” he explained. “These really high prices we’ve seen lately will have more to do with next year’s crop than this year’s crop, except for spring wheat, spring canola or any pulses that were planted. They are all affected by fertilizer prices from just five or six weeks ago.”

In early June, fertilizer prices dropped slightly, primarily because of reduced demand. Producers across the U.S. are having such a hard time getting their spring crops planted that they aren’t buying fertilizer because they can’t get out to their fields to use it.

Will the high wheat prices continue? Fortenbery is keeping an eye on the red wheat crop, which is expected to yield below average due mainly to drought. For white wheat, he says it’s too early to know.

“If the weather continues like it is and we get some heat and we have a great white wheat crop, white wheat prices could go down even as red wheat prices go up. We could also end up being too wet, and if we don’t get some heat and dryness so we can get in a harvest by August or July, then maybe wheat quality ends up being a problem. It’s a little hard to say right now,” he explained.