This Wonderful Place Zane Grey's Northwest and the Desert of Wheat

2025February 2025

By Richard Scheuerman

Special to Wheat Life

Best-selling Western author and conservationist Zane Grey (1872-1939) is considered the father of the modern Western novel. He wrote some 300 short stories and 80 books. Grey’s writing was known for idealizing the American frontier spirit with archetypal characters inhabiting moral landscapes who exemplified the Code of the West — integrity, friendship, loyalty. These attributes are also vividly expressed in Grey’s remarkable 1919 best-seller about Columbia Plateau rural life, “The Desert of Wheat,” which weaves rural romance and Northwest farm life against the backdrop of labor unrest and World War I.

In July of 1917, Grey, his wife, Dolly, and several companions journeyed through the region during a trip to Glacier National Park and the Pacific Northwest. Many of the places in “The Desert of Wheat” were based on places the Greys visited in Eastern Washington. Historian Richard Scheuerman has written about Grey’s visit. Photos of the trip that appear here were discovered in a scrapbook bought at auction by a collector. The scrapbook was donated to the Zane Grey West Society and later donated to the University of Oregon’s Knight Library Special Collections. Here is an excerpt from Scheuerman’s paper, “This Wonderful Place: Zane Grey’s Northwest and The Desert of Wheat.”

Grey begins “The Desert of Wheat” with soaring prose that moved a contemporary Boston reviewer to comment, “His opening landscape lingers in the mind: nobody has so painted just that scene.” To be sure, few American novelists of prominence had ever visited the Inland Pacific Northwest, but Grey’s “pictorial sense” was the full measure of any who could conjure a mystical terrain laden with grain and earth: “A thousand hills lay bare to the sky and half of every hill was wheat and half was fallow ground, and all of them, with the shallow valleys between, seemed big and strange and isolated. The beauty of them was austere, as if the hand of man had been held back from making green his home site, as if the immensity of the task had left no time for youth and freshness.”

The book includes numerous references to actual places across the Columbia Plateau, like Spokane, Connell, and Kahlotus. Fictitious communities are also named but with sufficient geographical description to indicate locations like Ruxton in Golden (Walla Walla) Valley and Neppel (Moses Lake). Grey also references the work of notable agriculturalists like Frederick D. Heald at the State Agricultural College and Experiment Station in Pullman, present-day Washington State University. Grey’s original version, now in the Library of Congress, also mentioned other communities including Ritzville, Odessa, and Marlin. Subsequent insight by local historians regarding the book’s principal families also sheds light on the inclusion of particular individuals and farms. Grey is thought to have visited areas in Grant, Adams, Whitman, and Franklin counties in 1917, and traveling from Pullman to Connell by train or automobile would have led through Colfax, Hooper, Washtucna, and Kahlotus.

Grey’s journal of the trip has not been located, so his exact mid-July itinerary and schedule cannot be documented with precision. But in 2019, a collector of Zane Grey fishing literature and lore acquired several of the author’s scrapbooks at auction, and one was of his and Dolly’s 1917 trip to the Pacific Northwest. The new owner kept the other items relevant to his interests and donated the Northwest collection to the Zane Grey West Society, a national organization devoted to the promotion of interest in the celebrated author. Among the scrapbook’s 50 photographs of Glacier Park and other locations were several showing the Grey party visiting Eastern Washington harvesting operations. One image shows them stopped in the rural hamlet of Wheeler several miles east of present-day Moses Lake, indicating they traveled from Spokane in automobiles to visit various unidentified locations in the region.

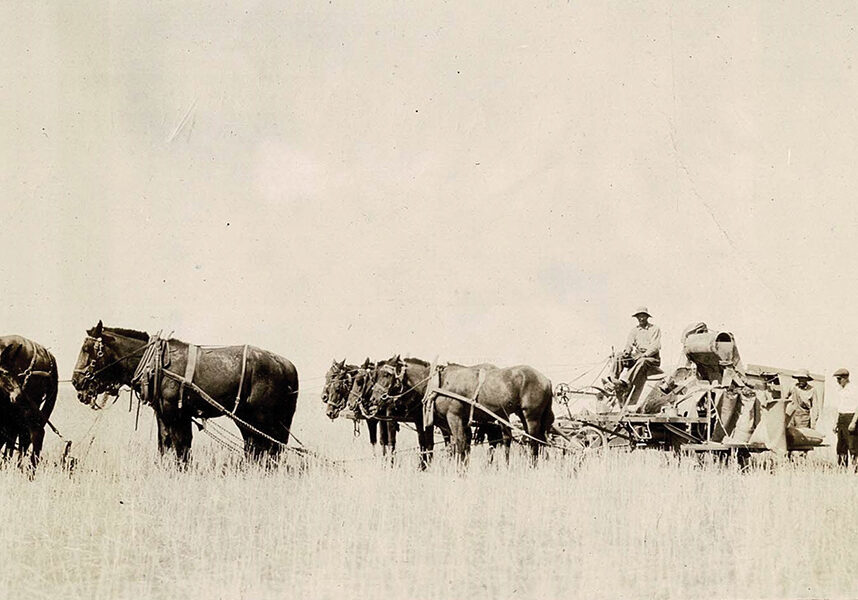

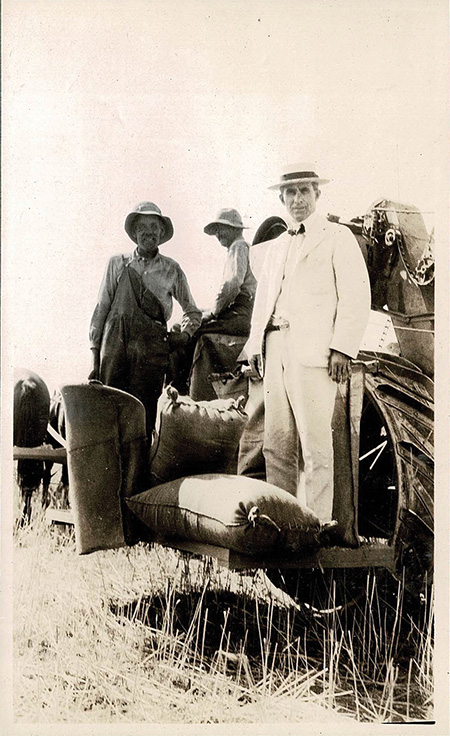

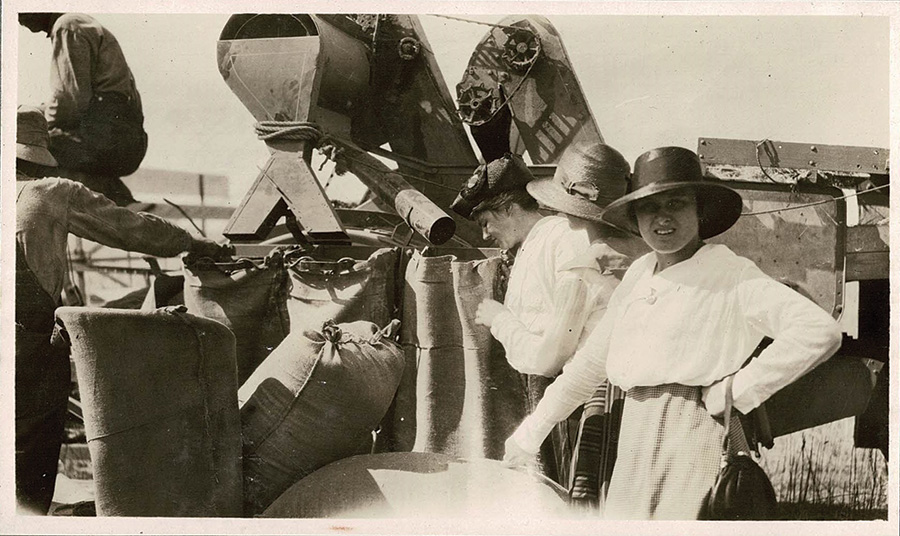

The photographs show Grey and the ladies exploring all facets of the work. They inspect the clean-grain elevator apparatus of a horse-drawn combine and the dusty work. The smiling, muscled sack-sewers and “mule-skinner” — the highly regarded “jerkline” driver of the enormous team of draft animals — were likely surprised and delighted by the visit of such distinguished guests. Another image shows a horse-powered push-header to cut the grain approaching a header-box wagon that would receive the cuttings and transport them to a nearby steam-powered stationary thresher.

The contrast between the formally attired Easterners and workers veiled in dust and chaff is striking. But they also attest to Grey’s interest in close-up inspection to better understand the people, machinery, and crops that would become core elements for “The Desert of Wheat.” Comparing Grey’s possible itinerary with travels in the book by the Dorns and Andersons and events reported in the local press suggests that some characters were composite figures drawn in part from the author’s personal interactions during his visit.

Much of the book’s action takes place at the Anderson-Dorn farm, a place of Grey’s imagination, but, according to local lore, modeled in part on a Franklin County ranch owned in 1917 by R. F. Anderson and located approximately nine miles south of Connell. (The property was later owned by the Kenneth Owsley family.) Like Lenore Anderson’s father, R. F. Anderson was a prominent local businessman who also owned property in the Walla Walla Valley. Connell had been platted in 1883 as “Palouse Junction” for a spur of the main Northern Pacific transcontinental line that tapped the fertile Palouse Hills grain district to the east. Later named Connell for a railroad official and pioneer resident, the town had long served as an important grain storage and transfer point with substantial timbered flat-houses along the rail line for storing sacked grain, a thriving main street business district, and local newspaper, the Connell Tribune-Register.

The tableland surrounding the Anderson farm would have presented Grey with a stunning vista with Oregon’s Blue Mountains to the east and flaming sunsets beyond the grass- and sage-covered Horse Heaven and Frenchman Hills rising in the west. The farmstead included a two-story main house that remains on the site and substantially conforms to Grey’s description of the Dorn home, numerous outbuildings, crenelated water tower and windmill, and a 60 foot by 110 foot barn that was enormous even by Big Bend standards. The property was situated along the area’s principal north-south “Central Washington Road” and had served in earlier days as a waystation for stagecoaches who tended and exchanged teams of horses in the capacious barn.

According to local tradition, Grey visited the Anderson place and spoke and witnessed harvest field labors firsthand. On July 20, the Tribune-Register reported on the commencement of field operations: “Harvest has begun already and will be in full swing here by the middle of next week. While the hot, dry weather has interfered somewhat with the later grain crop, the fields which matured earlier are in splendid condition and promise a good yield.”

Grey, the meticulous researcher, gleaned material for the new book throughout his July journey and visits with Northwest farmers and rural community residents. The travelers then boarded the train for Portland and connections to California. The route down along the lower Columbia River took them literally beneath the shadow of railroad tycoon Sam Hill’s imposing Maryhill Ranch House high on a forlorn bluff near Wishram. Hill, who had been raised Quaker, had spent lavishly on the mansion and envisioned a nearby farm colony of residents similarly devoted to the principles of nonviolence. The remote location prevented fulfillment of Hill’s dreams, but he did construct the nation’s first World War I monument a short distance east of Maryhill. The structure, dedicated on July 4, 1918, and completed in 1926, is a full-scale replica of ancient Stonehenge, which Hill had visited on one of his many visits to Great Britain.

Richard Scheuerman was raised on the family farm near Endicott, Wash., and graduated from Washington State University in 1973 with degrees in history and education. He served for 35 years as a public school teacher, administrator, and college professor. Scheuerman retired from education in 2015 and then directed the Franklin County Historical Society and Museum in Pasco, Wash. His most recent creative endeavors have included the “Harvest Project,” a three-volume study published by Triticum Press on agrarian themes in world art, literature, and music. Scheuerman plans to publish the full manuscript of “This Wonderful Place: Zane Grey’s Northwest and The Desert of Wheat” in the near future.