Atmospheric scientist sees chance for above-normal precipitation through rest of year Forecast for fall

2021October 2021

By Trista Crossley

Editor

After one of the driest crop years on record, can Pacific Northwest growers expect an equally dry fall? Eric Snodgrass doesn’t think so.

“When we look at the longer-range models and when we look at what’s going on out in the Pacific Ocean, there are no strong signals suggesting we will have a drier October/November,” he said. “What’s helping that along is there is a La Niña redeveloping in the central Pacific. When we look back over the last 70 years, we have a much better chance of having above-normal precipitation through the front half of winter if there is a La Niña evolving. Generally speaking, that will be good for the winter wheat sowing. That will also help the crop germinate and get going before dormancy. There’s a pretty positive vibe overall about what this upcoming fall is going to look like.”

Snodgrass is the principal atmospheric scientist for Nutrien Ag Solutions. He produces a weekly weather update video for Northwest Farm Credit Services that focuses on the Pacific Northwest. Those videos can be found at northwestfcs.com/en/Resources/

weather-insights. He also offers daily weather updates; growers can sign up for those at info.nutrien.com/snodgrass_weather.

In the Pacific Northwest, La Niñas—they usually happen in pairs—typically bring increased snow to the mountains. A La Niña develops when central Pacific Ocean temperatures are cooler than normal. Last winter’s La Niña was considered a moderate one. For this winter, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) gives an 80 percent probability that a weak La Niña will develop, meaning it will have less of an influence on the jet stream.

“You can have years where you see cold ocean temperatures, but the atmosphere doesn’t behave like it’s a La Niña,” Snodgrass explained. “I would say this means the likelihood of us having a really cold and really snowy winter, which is what often happens with La Niña, is minimized a little bit. But there’s no indication that we are going to have a major drought. That’s important as well.”

Growers in Eastern Washington got a little relief from the drought in September. According to the National Weather Service, through Sept. 20, the Spokane area had received .68” of rain. The Pullman area had received .44”; the Ritzville area .18”; Davenport area .45”; Asotin area .31”; Wilbur area .67”; and Prosser .47”.

But even with the September rain, seeding conditions around Ritzville stink, according to Aaron Esser, Washington State University Extension director for Adams County.

“Around Ritzville, they are getting some stuff up, but you don’t have to go too far west of Ritzville where they aren’t going to seed until it rains or they are forced to by crop insurance,” he said, adding that while the September rain was welcome, it created crusting problems for some growers who had already seeded.

At the Lind Dryland Research Station southwest of Ritzville, Station Director Bill Schillinger said this was the fourth driest crop year (Sept. 1 through Aug. 31) in the station’s 106-year history.

“Seeding conditions are really rough,” he said. “We haven’t planted anything but winter peas at Lind. Neighbors haven’t planted much around us. Mostly what I’m seeing is farmers who haven’t seeded at all or those that have tried and quit.”

Schillinger said anything that has been planted was planted extremely deep to try to reach moisture, and he expects to see a fair bit of reseeding happening.

Conditions aren’t any better in the Palouse and southeast Washington. Stephen Van Vleet, regional Extension specialist based in Colfax, said farmers are anxious to get planting after getting some moisture.

“I don’t think that’s a very good idea,” he said, explaining that the amount of rain (so far) isn’t enough to meet up with any existing moisture that is 8 to 10 inches below the surface. That dry zone could leave the seed vulnerable to disease.

Wheat farmers are facing a crop insurance planting deadline of Oct. 31. Any wheat planted after that date is ineligible for crop insurance, so if they must, farmers will “dust” the seed in and wait for rain, Schillinger said.

“The late-planted wheat always does worse than early planted. It’s all a matter of when you get the crop established,” he said. “If fall rains start by mid-October and they keep coming, farmers can plant at a shallow depth and go for it. The sooner you get established, the better you are. Any delays in plant stand establishment will reduce grain yield potential.”

Van Vleet has done studies in the Palouse that show a yield loss tendency in wheat planted after Oct. 15. The decision when to plant could come down to weighing a potential yield loss against reseeding costs if the wheat is planted and disease or crusting issues occur.

“Reseeding 5,000 acres is more expensive than losing a few bushels of yield,” he said. “It’s tricky. If they keep getting moisture, they’ll be fine. If not, they won’t.”

But even if Eastern Washington gets the average fall precipitation at the normal time, farmers won’t be out of the woods yet. The hot, dry summer has left the soil bone dry.

“We are way down (in soil moisture). Three to four inches down over average. That’s really tough to make up,” Esser said.

What happened in 2021?

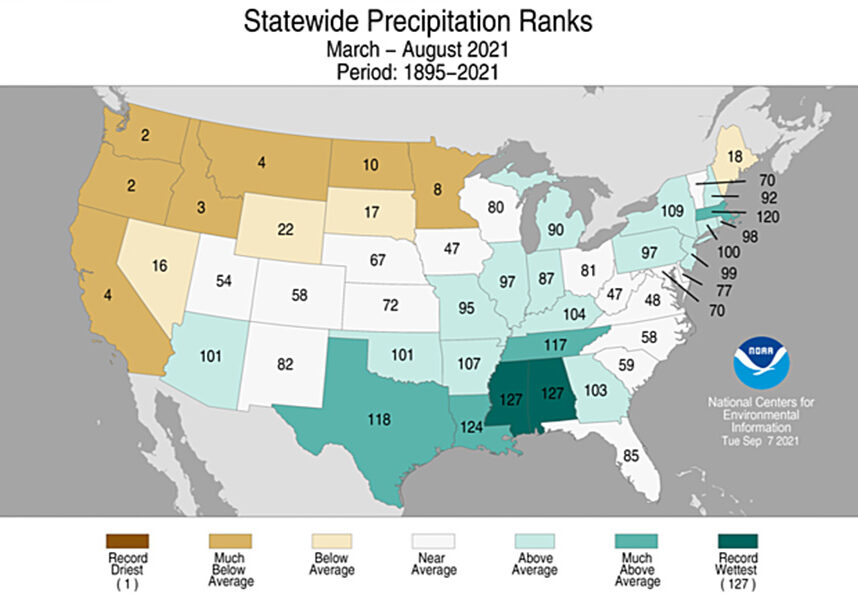

Talk to the old-timers, and you’ll hear them say it hasn’t been this dry since 1977. According to NOAA, March-August of 2021 ranks as the second driest period on record in Washington since 1895. But last spring, very few people, including Snodgrass, thought the available data predicted a drought.

“We were not expecting the events that really took shape in June that lasted into early August to be quite as pronounced as they were,” he said. “That was actually quite anomalous and rare given that ocean temperatures were still cool off the coast, and there was quite a bit of warm water in the north Pacific. But the atmosphere just preferred a massive ridge over the Northwest. It got very hot and very dry, and the fire season started early. It was a rough go of it this summer.”

Snodgrass said the drought conditions were set up by a self-sustaining ridge in the jet stream that parked itself over the Pacific Northwest and created a heat dome. That ridge pushed moisture away from the Pacific Northwest, the northern Plains and the Canadian prairie and into the Midwest. The ridge didn’t start breaking down until mid-August.

“I told the Canadians this spring that if we do see a southwestern ridge develop, you tend to get lots of storms that run around the edge of it. But it wasn’t a southwestern ridge; it was a northwestern ridge. It pushed everything out of the way, and the net effect was pretty nasty,” he said. Wheat and barley yields throughout the region suffered. Unfortunately, that extreme weather may become less of a freak occurrence and more of a regular event.

In a study published in 2018, researchers looked at 70 years’ worth of data and concluded that there is a higher probability that we’ll see more of these type of ridges over the Northwest in the future. Snodgrass’ own research backs that up. He said there’s been approximately 3 degrees F of warming in the Northwest during the warm season since 1950.

“That means that we’ve kind of shifted the base state a little bit, so it tends to favor more of these kind of extreme events when they do happen,” he explained. “It doesn’t mean it won’t get cold ever again, and it certainly doesn’t mean it will stop raining. It just tends to say we have better chance of having those kind of events occurring. It’s something, in any given year, you may not get the full effect of, but when you look over a decade or two or three decades, there’s a trend there that we can’t ignore. The net effect is these changes need to be understood. They need to be observed, and we need to make sure that we have adaptation practices and mitigation practices in place so it doesn’t get to an unsustainable point.”