On Impact Harvest weed seed control gives growers another tool in battle against weeds, herbicide resistance

2022December 2022

By Trista Crossley

Editor

For the past four years, Mader Enterprises has been practicing harvest weed seed control on their farm near Pullman, Wash. In late October, area growers gathered at Greg Mader’s farm shop to hear some of the things they’ve learned and to meet one of the experts on harvest weed seed control, Dr. Michael Walsh, an associate professor at the University of Western Australia.

Joe Limbaugh (second from left) with Mader Enterprises talks to a group of growers at a meeting at the farm’s shop about their experiences running the Seed Terminator, an impact mill that destroys weed seed during harvest.

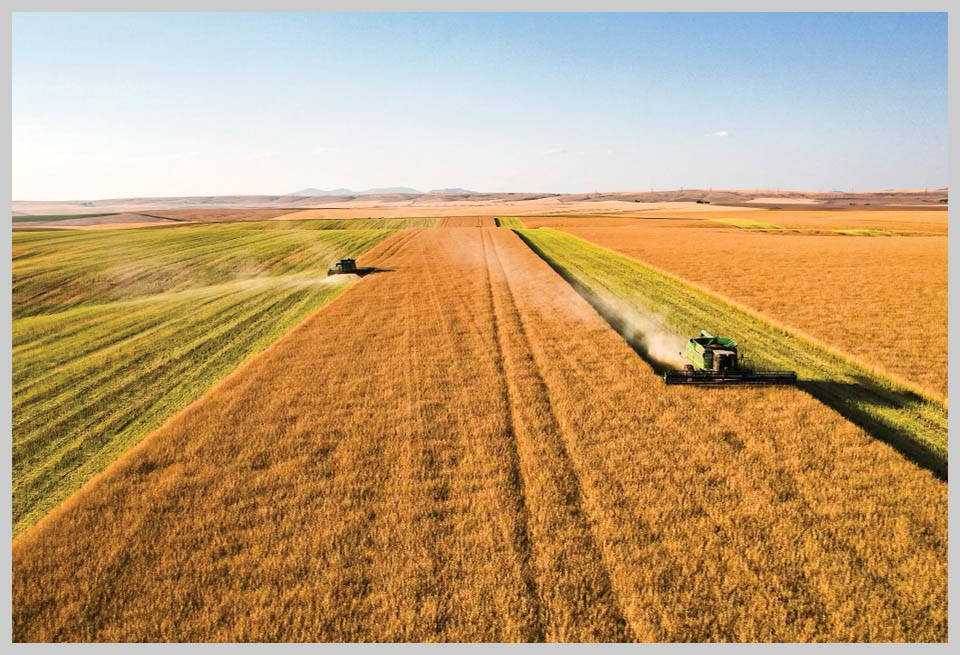

The meeting, organized by Drew Lyon, weed scientist at Washington State University and a frequent collaborator of Walsh’s, focused on the Mader team’s work with the Seed Terminator, a device installed on the back of a combine that destroys weed seed by funneling chaff through an impact mill. Lyon said the meeting was a good opportunity to show Walsh how the impact mill technology works in the Pacific Northwest.

“The Palouse is a high production area. We’ve got hills. Australians tend to have a lower production and not so many hills. So what have they (the Mader team) had to do to modify the system and make it work here?” Lyon said. “I just thought it would be a neat way for him (Walsh) to learn about the systems, these mill systems that are here, how are they working, and how might they need to be set up differently than he’s used to.”

Joe Limbaugh with Mader Enterprises told growers that the first year using the device, 2019, was a “year for learning.” Among other things, they learned that chaff is fluid, but straw is dense compared to the standard Australian harvest conditions. They also learned that the impact mill doesn’t like green material. They were able to deal with that by changing cutting height (for field horsetail) and switching screens to improve the impact mill’s performance when cutting green-stemmed material, such as canola. Limbaugh said that switch lowered the efficacy rate for ryegrass from 99% to mid-80%, but destroyed nearly 100% of canola seed, which decreases volunteer canola in the following winter wheat crop.

The Mader team has also learned that by planting earlier-maturing crop varieties, they are able to capture more ryegrass seed in the impact mill.

“Overall, we feel that the technology is promising and is showing positive results, especially in our winter wheat rotation,” Limbaugh said. Due to both percentage of seed capture and seed dormancy, the company behind the Seed Terminator expects growers will need three to five years of running the multistage impact mill before seeing significant results.

“The seed bank is full and is similar to interest in that it keeps building, although when it comes to making our preplant Roundup application in the spring, it is definitely looking like there is a reduction in the numbers of rye. Now, is that attributed to weather, and we aren’t seeing the flush yet? It’s hard to say,” he explained.

The Mader team has been running the Seed Terminator across all of their crops, which has included winter and spring wheat, spring barley, canola, peas and lentils. They’ve found they’ve needed to reduce their normal cut height in wheat and barley to ensure weed seed capture, which slows harvest a bit. Fuel usage is up as the device draws an additional 80-120 horsepower depending on the conditions. They feel the trade-offs the device requires are worth it, especially since the combine is the biggest weed seed spreader.

“From an agronomic standpoint, we are dealing with a massive reduction of volunteers. We don’t see the amount of green bridge that we used to. The green bridge we see today is usually from the combine operator pushing the limits of the grain tank and spilling,” Limbaugh said. “The reduced volunteer has allowed us to go from a blanket preplant Roundup application to a spot spray application on our canola ground. This past spring, we only sprayed roughly 25% of our canola ground. We feel this not only is a money saver, but also allows us to get across the ground quicker, improving our chances of seeing a higher yield but also preserving the glyphosate trait.”

Dr. Michael Walsh, an associate professor at the University of Western Australia and an expert on harvest weed seed control, attended a meeting of growers outside Pullman to talk about his work and hear how Pacific Northwest growers are using harvest weed seed control.

Practice widespread Down Under

Walsh has seen firsthand the struggle to control herbicide-resistant weeds. Farmers in Australia have been dealing with this issue since the early 2000s, leading them to investigate alternative methods of weed control.

“We’ve had extensive resistance across landscapes at very high frequencies, 80 to 90% of weed populations are resistant to several mode of action herbicides,” Walsh said. “It just forced us into change, to try different techniques.”

Walsh is currently in the U.S. as part of the Fulbright Program to work with U.S. researchers and growers who are just starting to investigate harvest weed seed control. In Australia, harvest weed seed control is mainly used in small grains, but in the U.S., the technology is being considered for corn, soybeans and even cotton. Walsh said adoption of the technology in the U.S. is still in the early stages, but there’s already been some clear differences in how harvest weed seed control will have to work in the U.S. vs. Australia.

“We’ve heard a few stories about green material causing issues with the mill systems, in particular, and that’s something we haven’t seen a lot of in Australia, so that’s a new learning experience,” he explained. “In Australia, at harvest time, it’s hot and dry. There’s no humidity, and so the weeds and the crops are pretty much dead or dying of drought, typically. We don’t often have a lot of green material, but it can occasionally happen in crops like canola, where we’ll have some green stem material.”

Besides the impact mills, there are several other types of harvest weed seed control (see sidebar). For farmers interested in experimenting with this type of weed control, Walsh recommends starting conservatively with a cheaper option, such as chaff lining, which concentrates the chaff (and weed seed) into a strip. The emergence of the weeds is an easily seen indication of how well it worked.

“So, if you see a big strip of green weeds coming up, you go, ‘oh yes, that’s obviously worked because there’s no weeds coming up in the areas surrounding that strip,’” he said. “Once you see that, it gives you an idea that it is going to work for you, and you can start thinking about graduating to something a little bit more sophisticated.”

Growing problem in the PNW

But how big of a problem is herbicide resistance, particularly in the Pacific Northwest? According to Lyon, critical in some areas.

“Here in the high rainfall area, Italian ryegrass is really changing how people go about doing what they are doing because they’ve had such trouble because there’s a lot of biotypes out there resistant to multiple herbicides. It’s becoming very difficult to control simply by herbicides,” he said. “Downy brome in the Walla Walla area. I’ve come across biotypes that are resistance to all the group 2 herbicides. They are really struggling to control downy brome there. This might be a tool that can help with that.”

Lyon advised growers to think about harvest weed seed control methods and “pencil them out.” Like Walsh, he explained that there are cheaper options than the impact mills that growers can start with. Lyon has collaborated with other researchers on several publications about managing herbicide resistance. They can be accessed at smallgrains.wsu.edu/herbicide-resistance-resources/.

“We’ve been very fortunate the last 30, 40 years to have highly effective herbicides, but we are losing them because we’ve overused them, and we just don’t have new stuff coming like we used to,” Lyon said. “People are going to have to start looking outside the herbicide solution to everything. We still have some herbicides that are really effective, but if that’s all we use, they won’t be effective for long.”

Methods of harvest weed seed control

As concerns over herbicide resistance increase, more growers are investigating alternative ways of reducing weed populations, including physical methods such as harvest weed seed control.

Harvest weed seed controls target weed seeds collected during harvest by managing chaff material. While developed primarily in Australian small grains production systems, the technology has the potential to be used where weed seed is harvested alongside the cash crop. As Dr. Michael Walsh, an associate professor at the University of Western Australia and an expert on harvest weed seed controls, explained at a recent meeting of Washington growers, if you can collect the weed seed at the front of the combine, you can deal with it on the back end.

According to a Pacific Northwest Extension publication, available at smallgrains.wsu.edu/herbicide-resistance-resources/, harvest weed seed control systems include:

- The chaff cart system. The chaff cart system is a trailing cart attached to the rear of the combine that collects the chaff material, including the weed seed, during harvest. The collected chaff is placed in piles that, for ease of management, are normally lined up across the field for subsequent burning, grazing or collection.

- Narrow-windrow burning. This system requires a chute attached to the rear of the combine that concentrates the chaff and straw into a narrow (20- to 24-inch) windrow during harvest. These windrows are subsequently burned prior to crop planting. Research in Australia and Eastern Washington has shown that 99% of rigid and Italian ryegrass seed in the windrow is destroyed by this method.

- The bale direct system. This system consists of a large square baler attached directly to and powered by the combine that builds bales from the chaff and straw exiting the combine during harvest. This system is reliant on available markets for the baled material. There are concerns over the removal of crop residues and the negative impact that has on soil health.

- Integrated impact mills. These devices fit into the body of the combine itself. Chaff material exiting the combine is processed by these impact mills to destroy the weed seeds contained in the material. The processed chaff is then spread back across the field. This is the only system fully compatible with many soil conservation practices that promote full straw loads returning to the field.

- Chaff lining and chaff tramlining. These are the newest harvest weed seed controls that are rapidly gaining popularity in Australia, due primarily to their low cost. Attachments at the rear of the combine collect and place chaff into narrow 10- to 12-inch rows, either between stubble rows directly behind the combine (chaff lining) or in the wheel tracks (chaff tramlining). Concentrating the chaff in narrow rows creates an unfavorable environment for weed seed germination and emergence. Those weeds that do emerge and grow are contained in narrow rows where they have little or no impact on overall crop yield.

One of the growers inspecting the Seed Terminator, an impact mill that is installed on the back of a combine.