Plotting a route Soil health road map informs state process, sets milestones

2021December 2021

By Trista Crossley

Editor

Leaders at the Washington Soil Health Initiative (WaSHI) now have a better understanding of the route ahead thanks to a recently released road map that outlines issues and concerns and sets milestones on the journey to improving the state’s soils.

The road map, available at soilhealth.wsu.edu/washington-state-soil-health-roadmap/, divides the state into eight focus areas, representing more than 5.4 million acres and covering approximately 72 percent of cropland in the state. The focus areas are:

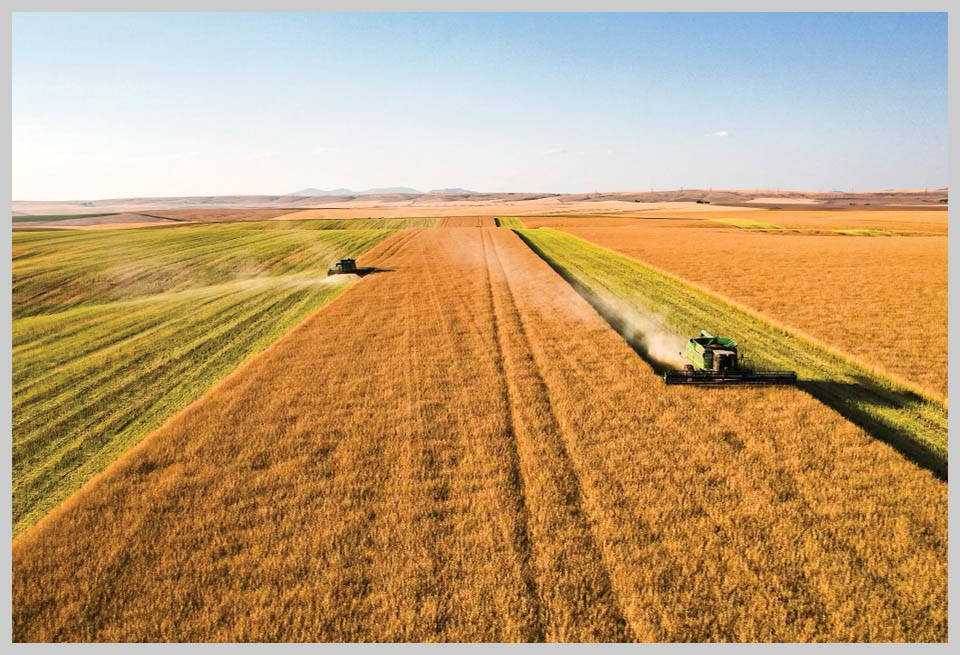

- Dryland agriculture in Eastern Washington.

- Irrigated Columbia Basin.

- Irrigated potato production in the Columbia Basin.

- Juice and wine grapes.

- Northwestern Washington annual cropping systems.

- Tree fruit.

- Western Washington diversified farming systems.

- The environmental community.

“With more than 300 crops grown in Washington, we weren’t necessarily going to be able to cover every single one of them,” explained Karen Hills, research associate at Washington State University’s (WSU) Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources. Hills was one of the lead editors of the road map. “The cropping systems that probably represent some of the most valuable commodities in Washington ag, like tree fruit and wine grapes, were each given their own group, in part, because there were specialists that work with those production systems at WSU. Some (cropping systems) were lumped together because of Extension expertise or region-specific crop rotations. Hopefully, most growers can find themselves somewhere in one of those groups.”

Hills said having a road map gives the people working on the WaSHI a “systematic way to assess what the goals and priorities were for growers” for each of the focus areas. Growers provided feedback through direct and indirect interactions, including virtual listening sessions, previous soil health events and needs assessments and through personal interactions with WSU staff, especially Extension personnel. That information was collected and organized by individual focus area leaders, followed by the editors pulling out key themes and identifying information gaps. The road map is intended to be a living document, and Hills said she expects it will be revisited and updated as necessary.

Despite the fact that Washington agriculture includes many different crops grown in many different soil types in many different ways, there were some common threads that emerged, particularly the need for a low cost way to measure soil health and establishing measuring metrics appropriate to specific production systems.

Some of the other common goals and priorities include easy access to equipment that maintains soil health, such as no-till seeders; improved knowledge of soil health specific to different production systems; improved information dissemination to agricultural professionals and producers; and a greater valuation of soil health in the marketplace.

Some of the soil health issues cited include soil pH, soil compaction, nutrient cycling, water-holding capacity, soilborne plant diseases and wind and water erosion.

Hills hopes producers see the road map as a starting point for engaging with the WaSHI and a way to monitor soil health research and experiments. The road map includes short-term (one to five years), medium-term (five to 10 years) and long-term (10 to 20 years) milestones to help gauge progress.

The decision to include the environmental community as one of the focus areas came about because the off-farm benefits of soil health—something that community tends to focus on—often doesn’t directly impact a producer’s bottom line. Hills feels including the environmental community viewpoint makes the road map stronger.

“It’s not common that these different viewpoints are incorporated into the same effort,” Hills said. “I think, in a lot of ways, the environmental community is sometimes seen as being at odds with agriculture, but I think in this case, there was a lot of understanding that producers really need to make the bottom line work for them and understanding that the return on investment (for soil health practices) may not always be clear, may not always happen over the short term. I was impressed with their level of understanding of the constraints under which producers are working.”

Rich Koenig, interim dean of WSU’s College of Agricultural, Human and Natural Resource Sciences, was the primary author of the section of the road map focused on dryland agriculture in Eastern Washington.

“The Soil Health Initiative road map is a guide for future research focus and investment. Dryland farmers should expect to see this road map translate into research priorities in the near future,” Koenig said in an email.

Some of the goals and priorities for Eastern Washington dryland producers include improved understanding of soil biology and plant interaction, use of additional off-farm inputs and better soil health assessment tools. Economic and sociological barriers and a lack of information were noted as roadblocks, with producers saying they could be overcome through improved research capacity, innovative extension/outreach methods and long-term investments in education.

For information on the WaSHI, visit agr.wa.gov/departments/land-and-water/natural-resources/soil-health.

What’s Next

While the road map is an important part of the Washington Soil Health Initiative (WaSHI), the three agencies involved are already moving forward on their respective pieces. At Washington State University (WSU), soil health leadership and faculty are being established, and researchers there are beginning to propose and set up research experiments. For more information on WSU’s focus on soil health, visit soilhealth.wsu.edu

At the Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA), Dani Gelardi, the WSDA soil health scientist, said the department is currently taking soil samples from across the state as part of their State of the Soils Assessment effort.

“We are taking actual soil samples and getting them analyzed for biological, physical and chemical parameters so we have a dataset that complements what we’ve learned,” she said. “The data will be rolled into a soil health database. People will be able to look at a map and search ‘carbon storage by crop’ or ‘nutrient bank by region.’ It’s a way to get the public more involved and educated about soils in the state.”

WSDA is also working on a soil health economic report to demonstrate how soil health translates to a grower’s bottom line. The goal is to determine the cost to implement a practice and if that practice makes economic sense to producers in different regions. For more information on WSDA’s role in the WaSHI, visit

agr.wa.gov/departments/land-and-water/natural-resources/soil-health.

The third agency, the Washington State Conservation Commission (WSCC), will take a more active role at a later stage of the WaSHI, but right now, they are looking to reconvene their soil health committee, which will play a vital role in disseminating the information gathered by WSU and WSDA.

“The initiative is an multiyear process. We are still figuring out the current (soil health) baseline, and where we want to be. Then we have to figure out how to best disseminate that information. That’s when the conservation commission and the conservation districts will jump into a much higher gear,” explained Alison Halpern, a scientific policy advisor for the WSCC.